- Home

- James Phelan

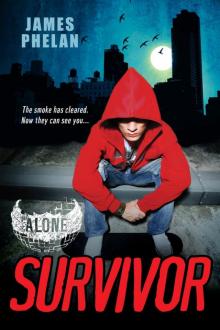

Survivor Page 2

Survivor Read online

Page 2

My throat gave out with “sick”; a croaking, hoarse, feeble cry, all I had after so many days of soliloquy.

I showed him my empty hands, how I was unarmed, on the ground, at his mercy. Yesterday, maybe I would not have been so willing to submit, but today, now, I wanted to live, to hear what he had to say, to learn what was out there, to somehow get home.

I pleaded softly, “I’m not the enemy . . .”

He reached down and I inched away, shuffling back in the wet snow from both the threat of his grasp and his pointed rifle, but he took a long stride after me and dragged me to my feet. He held me up by my collar, at arm’s length, shaking me to see how I’d react. I didn’t fight him. His three colleagues stood beside the pair of all-terrain trucks with their monster-sized tires and stared.

This man who held me turned around and shouted: “He’s not sick.”

“So?” one of his colleagues replied as he climbed back into the truck. Visible through the open back flap of the canvas-topped truck was a container the size of a small car with USAMRIID stenciled on the side of it.

“They said they were all sick . . .” the soldier holding me said quietly to himself, dangling me in midair, his gaze locked on mine.

“Forget him!” The shout rattled around the empty street. “We gotta hustle.”

“Shoot him!” yelled another. “Do the kid a favor.” He slammed the cab door of the second truck and it motored off in the cleared wake of the first.

The last soldier remained, watching closely from the other side of the street, cradling his rifle. If this one here doesn’t kill me, that one will, won’t he? I swallowed hard. Should I run? Twist away and run? Zigzag my way around debris and hope they miss?

“Please . . .” I said to the one who held me. He had a name tag on his vest: STARKEY. “Please, Starkey, I’m not sick. You can’t kill me.”

“Kill him!” The order echoed across the street. Guns entitled men to do anything. They were clearly Americans, so why shoot me? Out of anger for what’s happened here? Out of fear? No, these were outsiders. They probably knew what was going on here, they had information. I was more afraid than he could ever be.

I pleaded with my eyes. I didn’t want to die, and now, more than that, I wanted to know. I wanted to talk, to ask questions, to listen and learn.

He let me go. “How old are you?”

“Sixteen,” I replied.

“We’re moving!”

“I’ll catch up!” Starkey yelled across to his buddy, who shook his head and remained standing there, rifle slung in his arms like a child. “Where were you when this attack happened?”

“Here.” I was too frightened to lie.

“Here in this street?”

“No,” I said. “A subway; I was in a subway.”

He nodded. “How many like you?”

“Like me?”

“Not sick.”

“I don’t know.”

“How many are you staying with?”

“Just me.”

“What?”

“I’m alone,” I replied.

I could see what he was thinking. That I was crazy. That I’d probably just crawled out of some blackened, deserted building, completely out of step with what was going on, a raving lunatic. No matter what stirrings of sympathy he may have felt, he couldn’t get away from the fact that I might just be mad and so, in my own way, just as dangerous as the infected people. Maybe I would have thought that too.

I tried to explain. “There’s this girl—Felicity. She might be in Central Park still. That’s where I’m heading. There might be others. I just haven’t seen anyone in person—”

“Well, kid, I’ve seen a lot. I’ve seen good people do things that don’t make no sense,” he said, not looking at me. “No sense. You understand?”

I nodded. He’d done stuff, too, probably.

“Soon there’ll be—there’ll be people coming through here, and it’ll get out of hand—it’ll be something you don’t want to see . . .”

“Why wouldn’t I want to see people?”

I’d dreamed of seeing people for twelve days . . .

He looked over at his comrades. Soldiers, on the road to nowhere. One of them turned, leaning from his truck window, and made a gesture to Starkey to hurry up. The vehicle had rounded the intersection up ahead.

“We’re getting left behind!” the other guy yelled, and finally moved on, jogging after his friend and then climbing into the second truck.

Starkey turned to leave.

“Who are you?” I asked him.

“I’m nobody,” he said as he held his rifle with both hands. “Just—just keep your head down, kid. Won’t be long.”

Won’t be long? “What won’t be long?”

He walked away. Square shoulders filling out his plastic parka. Hope departing. Just like that. No answer.

I ran after him. Fell into step beside him. His eyes scanned the street. The guy’s expression was stone. He looked down at me like I was nothing. Like I, and all this around us, was too big a problem for one man and his buddies to deal with.

“Don’t make me stay here,” I pleaded, falling into step beside him, heading for the departing trucks. “There’s thousands of those infected—”

“They won’t last much longer,” he said. “They’ll become ill and worse due to injury and exposure, lack of nutrition, all that. They can’t last long on just water . . .”

“No, you don’t understand, there’s another kind of infected—”

“I’ve seen, kid,” he said, zipping his collar up tight against a horizontal snow drift. “There are two clear groups of the infected. Yeah? I’ve seen that. Those who are literally bloodthirsty killers, and those who are content with any liquid to survive. Either way, both groups need fluid constantly; got themselves some kind of psychogenic polydipsia, they need to drink. It’s the why that bothers me—why the two different conditions . . .”

He seemed lost in the thought, a thousand-mile stare.

“That’s why you’re here?”

He eventually shrugged in reply.

“Maybe the ones who chase after people were already screwed up?” I said. “Murderers and criminals, stuff like that.”

“Maybe, kid,” he said, looking at his trucks. “But I doubt it.”

“They’re driven to kill for blood,” I said urgently. “I’ve seen them. They prey on others, take advantage of them. They’re getting stronger while the rest—the general population of infected—are getting weaker. The gap is growing bigger. The weak congregate, for safety maybe. They flock to where there’s easy water, they make do. The strong are in smaller packs, plenty are doing it alone, and they’re as strong as they were on day one, maybe even more so.”

“The ones just drinking water will die out if they don’t start getting some nutrients in them,” Starkey said. “Hell, we’ve already seen plenty who hyper-hydrated to the point of fatal disturbance in brain functions.”

“The others?”

“The others . . .” he shrugged. “Well, they might just be around forever.”

3

“Where does that leave me?”

WHe kicked at an empty drink can in the snow, looking pained. “Just go,” he said. “Soon as you can, whether you find your friend or not. Get out and don’t stop until you find someplace safe.”

When the explosion happened, I was full of homesickness for Australia. Would it be wrong to turn my back on New York now, when it needed me most? For all I knew Felicity was alone out here somewhere . . . could I just leave?

Was there anything left of New York to see before I went back? Dave said his parents lived somewhere out near Williamsburg. Maybe there was still time to go and see his folks, check on life beyond this island. To tell them what a mate he’d turned out to be in the end. Or was that part of my past, never to be revisited? I knew that to survive, I had to think of the future.

“Keep heading north,” the man was saying. “Far as you can.�

�

“Are you sure?”

“I sent my family to Canada. That’s as sure as I can tell you I am.”

“Canada’s okay?”

“That’s what I last heard.”

“What about Australia?”

He slung his rifle over his shoulder, adjusted the strap, then put his hood on.

“Please,” I said, “if you know something—”

He shrugged. “I’ve heard nothing beyond what’s here and now in my backyard. That’s a big enough problem for me. Just head for somewhere upstate at least. Hole up, find others, a town or somethin’, safety in numbers. Keep off the major roads in your travels—there’ll be more like us and worse.”

He looked down at his feet, then across at his buddies in their big-wheeled trucks, now passing through the next intersection.

“Why north?” I asked. My breath fogged in front of me, fast jets of steam.

“This illness,” he said, looking down at me, “it does better in the heat. Lives in the air, on the ground, stays active longer, stays alive, you understand?”

“No, not really.” I didn’t want to sound dumb, but I felt I had to know, whether or not he took me seriously enough to explain.

“The biological agent is still a threat, see? The cold kills it, it can’t live without a host for long.”

“How long?”

“I’m not sure. Days, less than a week.”

I hoped a week would be long enough to find Felicity and the others, to persuade them to come with me. Safety in numbers, right?

“But we’re leaving now,” Starkey said, as if reading my thoughts.

Was that an offer?

“I can go and check on Felicity, if you wait here. I’ll be quick.”

He shook his head. “Can’t take no baggage, sorry, kid. I gotta go.”

I thought fast. Could I give up on my hope of finding Felicity—so fast, so easily? “If it’s a problem to wait . . .”

I mean, could I even be sure that she actually existed, anyway? She could just be another illusion like Mini, Anna, and Dave. How could I trust myself after being alone all this time? Starkey hadn’t looked as if he believed me, that’s for sure. It’d be stupid to let this opportunity of rescue, of safety, to slip through my fingers because I’d run off to find someone who wasn’t there.

Then again, if I found Felicity and came back, Starkey might not be here because he didn’t exist either. But this had to be real, didn’t it? I couldn’t have made up what he was saying about the chemical agent. About all that noise and shooting just now . . .

I shook my head clear. No, Starkey was real. Felicity was real. The choice was real.

“Please, can’t I come with you now?”

“No.”

I was about to argue the point when he grabbed the front of my coat, held me, almost in the air. I waited for him to toss me to the ground or yell in my face.

“You find some other survivors like you ’round here like I said. You stick with them and head north, far as you can. You follow us and you’re dead. Ain’t nothin’ more I can do for you, same as there ain’t nothin’ I can do to stop my guys from protecting themselves if they see you as a threat.”

“That’s why you can’t take me?”

“That and more.” Starkey put me down. I no longer thought any of them were really military guys—they didn’t fit the part. American soldiers wouldn’t leave me like this. They wouldn’t look like this—uniforms, sure, but not with the different haircuts and weapons and stuff. His backpack was like the one I had for school. They looked about my dad’s age or older.

But none of that mattered. None of them turned around. No one seemed to notice me, not even my guy Starkey. They left me standing there, alone.

4

So I followed them, carefully keeping out of their way. A block. Two. On the third, they stopped and sent one of the men ahead on foot. The next intersection was impassable, even for their heavy trucks. They could push vehicles aside, one by one, but here was what remained of a tall building, now a three-story mountain of jagged rubble, covering the street. There was a lot of arguing and pointing, as they looked at what must have been maps or aerial photographs to find another route to wherever they were headed.

I kept checking over my shoulder, but there was nothing, no Chasers. Wherever they were, they weren’t out in the open today. But I still felt their presence, always there, lurking, watching, hunting.

The wind died down and it started to snow more heavily. Silent curtains of falling white powder. The clouds were dark. My neck and face were numb, my feet frozen. I sheltered in an alcove across the street and watched the convoy. They were shiny new monsters of things, jacked up on high suspension with chunky tractor tires eating into the snow. But the tops of the trucks—the hoods and canvas cargo covers—had been spray-painted white, for camouflage, I guess.

The men continued to argue among themselves. The driver of the second truck was guided by the driver of the first, who now stood on the roof of a crashed taxi, pointing to an easy path to clear.

The drivers got back into their cabs, and the first truck inched steadily forward, creating a path through the rubble mountain that seemed impassable from this vantage. Not even a couple of dozen cars and vans in the tangle could stop it from pushing on, its chunky tires never losing traction. They’d be through in maybe ten minutes. I’d forgotten the kind of power and freedom that a decent vehicle can provide. My twelve days of trekking and exploring had been limited to what I could achieve on my own two legs with the occasional help of a standard police car that I’d called my own.

While the first truck ploughed on, a couple of soldiers went into the lobby of a nearby office building, set up a propane burner, and put some water on the boil. Starkey crossed the street, headed my way, stopping a few paces before me. He was silent, as if he couldn’t bring himself to tell me to beat it again. He pushed some snow off a bench and sat down.

The more time I spent with him, the less like a soldier he seemed. His eyes may even have been kind—they were not hard, not mean or evil.

“Thanks for before,” I said, and sat next to him. “My name’s Jesse.”

He undid his coat’s collar. “I don’t want to know that.”

He looked back at his buddies. One walked over, passing him a tin cup of steaming coffee. This soldier, short and stocky with big bloodshot eyes, was all anger, all simmering rage, keen to take the fight to someone. I knew that feeling.

I said to them, “Try heading west two blocks, then down—”

“If I wanted your opinion I’d have asked for it,” the hostile guy snapped.

“I only—”

“You’ve got a big mouth, kid.” He shot Starkey a look before walking back to his friends.

Starkey passed me his coffee. I turned it down and he said, “Not from around here, are you?”

I shook my head.

“You were here on holiday?”

“Something like that,” I replied.

“Well, aren’t you right out of luck.”

“Where’s the help?”

“You’re lookin’ at it.”

“Serious?”

“Yep.” He took off his gloves and placed them on the ground.

“Then I sure am out of luck.”

He nodded, sipping the steaming brew through his thick gray moustache. The snow caught in his stubble and softened his appearance.

“There’re some roadblocks farther up on the major arterials leading outta here; that’s about as much a response to this as I’ve seen.”

“Where’s the government?”

“That’s a million dollar question, kid,” he said.

“So what about the roadblocks?” I said. Something shifted in my stomach: butterflies, excitement, possibility. “Does that . . . What does that mean?”

“Means roads in and out are blocked.”

“But, it means other places are okay outside of New York?”

“No, kid,

it’s not just here. Like I said before.” He looked up at the sky, squinted against the glare of the dull sun hiding behind a dull gray sky. “They’re up there, too. Watching. Counting. Got drones and whatnot buzzing around. They’re just trying to contain the worst of this wherever they can, see?”

No, I didn’t. I had a million questions. “You got through. How’d you get here, onto Manhattan? The bridges are down, the tunnels are . . .”

He nodded.

“Because you guys are soldiers?”

He smiled. “I look like a soldier?”

“You’re dressed like one.”

“We found a way around,” he said. “Wasn’t easy, though. Trucks helped, guns too.”

I tried asking again. “What are you doing here?”

“Doesn’t matter.”

“I don’t think you’d risk being here if it didn’t matter,” I probed.

“I mean it doesn’t matter to you.”

Okay. It wasn’t so much what he said as the way he said it. Everything mattered to me: any sign of life, any ray of hope. He wasn’t going to understand that, though, not in the few minutes we had to talk. I imagined what it would be like to be in the back of their truck, protected. They’d do whatever they had to do here and then we’d all leave, go someplace where it was warm and the people were friendly and there would be news and answers.

“Is this war?”

“We’ve been at war for a while now,” he said. He squinted at the demolished high-rise on the block and there was real anger there. “This is the next step. Difference is, the frontline is now here; right here on our doorstep.”

Which war? On terror? In the Middle East?

His friends hollered to him. The break was over, they were moving out.

“Look, I gotta go,” he said, slapping me on the shoulder, looking in my eyes like my dad had when he’d said good-bye to me at the airport. “Keep safe, kid. Keep your head down.”

“No! Wait! So, this roadblock, it means there’s heaps of uninfected out there?”

“Because of a roadblock? No.” One glove, two. “Like I said, they’re doing that to keep the worst of everything here in this place. You got a massive congregation here, millions of people packed dense, no telling what’d happen to small towns out there that might so far be uninfected if they—all these contaminants—get out of here.”

10

10 3

3 Survivor

Survivor 6

6 The Hunted

The Hunted Quarantine

Quarantine 11

11 The Last Thirteen - 1

The Last Thirteen - 1 Fox Hunt

Fox Hunt 9

9 7

7 Patriot Act

Patriot Act 2

2 Blood Oil

Blood Oil Red Ice

Red Ice Chasers

Chasers Liquid Gold

Liquid Gold 8

8 5

5 The Spy

The Spy Kill Switch

Kill Switch Dark Heart

Dark Heart