- Home

- James Phelan

Quarantine

Quarantine Read online

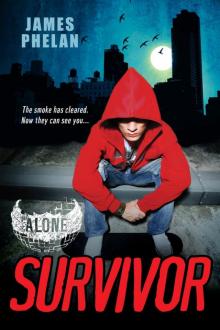

ALONE Series by James Phelan

Chasers

Survivor

Quarantine

QUARANTINE

ALONE

JAMES PHELAN

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Also by

Title Page

Dedication

Praise

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

later . . .

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FROM IDEA TO BOOK . . . - James Phelan on the conception of the Alone trilogy

Copyright Page

This book is dedicated to the memory of

Sgt. Brett Wood,

a magnificent soldier and a true friend.

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were; I have not seen

As others saw; I could not bring

My passions from a common spring.

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow; I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone;

And all I loved, I loved alone.

—from “Alone” by Edgar Allan Poe

1

We buried the snow leopard in the morning. The three of us stood in the mist that came with the winter’s dawn, the empty streets of Manhattan as quiet as they’d ever been since the attack. The lonely gray light sucked the color from everything but it was all we had to work by as we dug into the earth. A dark stain of frozen soil covered the animal’s mate, who we’d buried just the day before, two lifeless forms in stark contrast to a blanket of fresh white snow.

It was Felicity who insisted on the funeral, not Rachel, the animal’s caretaker. Maybe it was Felicity’s way to keep me here a bit longer, in the hope I’d change my mind about going; or in the hope that while I stalled here a miracle would come—rescue by whoever was left. Not that we knew who was left, not for certain. That’s why I needed to leave the safety of these fortified zoo grounds, yet again. Exploring the unknown was our best chance for survival.

In the snow-leopard enclosure of Central Park Zoo we held a little ceremony of sorts, silent and stoic. Felicity didn’t cry but Rachel did—just falling tears, no sound of sobbing. My two fellow survivors, standing next to me, remembering these beautiful animals that had never done anybody any harm, killed by violent figures in the night, those with an unquenchable bloodlust.

There was a bang-crash of a building coming down, probably nearby on Fifth Avenue.

“That was close,” Felicity said, spooked.

I nodded, words obliterated, for the sound had roused all the animals left in the zoo, waking them from their mournful chorus into a symphony of alarm, as if they knew that their tickets out of this life were loosely hanging chads.

“I hate it when they do that,” I said, close to Felicity’s ear, the cries of the birds and the sea lions assaulting my own. It was like trying to hide from Chasers near a car and setting off the alarm—it drew unwanted attention. In a silent city, we were now clearly in focus. “On such a clear morning, this sound’ll carry all through the park . . .”

So far this morning the Chasers had stayed away, as if out of respect for the properly dead. I was kidding myself by thinking that—they didn’t need emotions, just as they didn’t need normal food or shelter or warmth. At least, that was true of the predatory Chasers, the infected who would hunt you down, the ones who’d survive. Ironically, those whose contagion was wearing off—who were technically getting better, their faculties returning—were worse off. By the time they improved enough to find food and shelter, it would be too late; if the aggressive Chasers didn’t pick them off, one by one, the harsh winter would.

If my friend Caleb was one of the weaker kind, I could search him out, look after him. But he was a bloodthirsty Chaser, and there was no reasoning with them, as I knew from experience. The only resolution to a conflict with them was death. Was there any hope for Caleb? Probably not. Could I give up on him? No.

My packed bag was on the ground. I’d been ready to bug out of the zoo when the leopard died, but now I had doubts. I felt guilty about wanting to leave. I’d tried my best to calm and soothe Rachel. She’d said harsh words, what I felt might be final words . . . and then all our conviction, on both sides of the debate, came undone with the sudden ceasing of a heartbeat.

How callous that sounds, but that’s what it had come to: the death of an animal and what came with that had kept me here.

At the thought of leaving, my body felt weak with exhaustion. This time, I told myself, it would be different. It had to be. All I had been doing these past two weeks since the attack was moving from one false touchstone to the other—from 30 Rock, to Central Park Zoo, to Caleb’s bookstore, looking for a safety that was no longer possible, if it ever had been. I told myself I was helping, I was doing good, getting one step closer to escaping, to getting home . . . when all I’d really been doing was retracing my steps. Now I needed to make progress, real progress, before—

Before what, exactly? Maybe the uncertainty was the worst part. About twenty percent of New York’s cityscape had been destroyed in the initial attack. But every day since then there had been new fires and explosions, buildings falling one by one, here and there, as if to remind us that there was more to come. There was another act—maybe several more—to be played out. They weren’t finished with us yet—whoever they were.

“You should sleep,” Rachel said, jolting me out of my thoughts.

Neither of us had slept in the night and we both had full days ahead. “So should you,” I replied.

“I’m not the one going out there,” she said.

“I’ll be fine.”

“Well, at least rest for an hour, then go.”

“I can’t,” I said. “There’s no way I can sleep right now.”

She wiped the back of her sleeve down her face, her breath fogging in the cold. We watched Felicity trudging towards the main building, heading off to rest. Or maybe she was giving me and Rachel time alone. I got the feeling that Rachel had something she wanted to say to me.

“Rach?”

She looked at me, her eyes wet.

“What’s up?”

“Jesse . . . you know it wasn’t your fault, right?”

“What wasn’t?”

“What happened to Caleb.”

“Yeah?” I said, crossing my arms around my chest. “Well, I brought us all together, didn’t I?”

“Jesse—”

“I coaxed him into finding out what had happened to his friend, his parents, so I have a right to feel just a little bit responsible.”

“Everything—everything you’ve been doing these past few days has been for us, for our survival.”

I’d tried to do the right thing. I’d spent so long denying the reality of events myself I could recognize the same behavior in Caleb. You need to feel it, I told him, remembering that I’d forced him to visit his parents’ place. He hadn’t been able to express the horrors of what he’d found but it was pretty clear he’d seen more than he needed to. It had reminded him just how much he’d lost�

��he lost everything; he’d lost it all.

Then I remembered.

“He—he ran to help that fallen soldier last night,” I said. “He ran into harm’s way, to help a stranger. I—I might have run away from the danger.”

“What are you getting at?”

“He ran to help. I didn’t. I didn’t know what to do. All I did was run. So when Caleb needed me—when he really needed me—I failed him.”

“But there’s nothing you could have done to prevent it.”

Her words hung in the air for a moment and my breath steamed in front of my face as I studied the newly disturbed dark earth and deep snow in front of us.

“You weren’t there, Rach.”

“It was beyond your control,” she said.

“You didn’t see that blank look in his eyes. You didn’t see him feeding on that dead soldier—drinking him, like some kind of wild animal.”

“But I know how you feel.” She looked at me hard. “Just like what happened to my leopards here; taken from me. Could I have stopped it if I were out here that night? No. They would have killed me too.”

“Caleb was protecting me, Rach. Don’t you see?” I walked around the enclosure. “It could have been me—it should have been me, if any of us. I’m the one who’s been itching to trek out of this damned city. I’m the one always pushing—”

“Jesse—”

“I can’t let it go. I can’t just forget him, lose hope for him—it’s as important to me as . . .”

“As?”

I leaned on a fallen tree that was scarred by big scratch marks from the leopards, and breathed through rising nausea. Rachel put an arm around my shoulder and said softly, “We’re going to get through all this. All of us—Caleb too.”

I nodded; I wanted to believe.

“He did what you’d do and what we’d do in the situation.”

I fought back tears. “You don’t know that.”

“Of course I do.”

She stood close to me, her body warm against mine.

“Thanks,” I said. I was glad that she saw it that way. I stood and she hugged me and we walked out towards the central pool.

I paused by the gates to the zoo, and adjusted the straps of my backpack. The weight of the loaded pistol in my coat pocket no longer gave me peace of mind or felt like a burden; it was just there, another appendage in this new world.

“Look, Jesse . . .” She looked sadder in that moment than at any time I’d known her. “I’ve known for eighteen days that I’d have to walk away from here at some point, leaving them to fend for themselves.”

“So that means—”

She looked from the caged animals to me.

“It means, yes, I’m ready.”

I smiled.

“Go find that group of survivors down at Chelsea Piers,” she said. “Find them, see if they’re willing to try getting out of this nightmare, with us.”

I could see Felicity standing at the bedroom window, upstairs in the zoo’s big old brick building, watching us down here.

“And what if Caleb was wrong about them?” I said. “Or—or what if they’re not there?”

“Then we try doing this on our own.” Rachel unlocked the gate, I went out and she locked it after me. She smiled, the bars between us. “They’ll be there, just as Caleb said; he was a good guy.”

“He still is.”

I turned and left my friends behind. Rachel yelled out, “Be careful!”

I headed out alone. Me and these streets. Eighteen days since the attack, eighteen days of avoiding death at the hands of the infected. I walked through the park. Rocks shifted in rubble underfoot and rats scurried from a dead body. How I hated this place.

2

Today had started out freezing and damp, and now a wall of wet snowdrift blew hard against me in a headwind. I headed southeast, under the heavy, gray February sky, with the wind blowing around me and frozen rain falling. I’d learned to feel this weather now. When heavy snow rolls in, darkness comes early, time gets lost. In the streets it was easy to be lulled into a false sense of security, deaf and blind to what might lurk in the silence and shadows. How would this day end? Would it be any different from the others?

To catch my breath, I took shelter in an alcove, not that different from one in which I’d sheltered from similar weather, with a girl. We’d kissed. Anna. My first kiss, right here in this city, from a girl I would never see again, sharing an act full of heat and stomach-turning butterflies I might never know again. She’d tasted of strawberries. I smiled at that memory, licked my cracked lips. I could almost taste it.

Like so many, Anna never got to go home. She was one of the first to be taken in this attack. At least it was quick. I had no idea if she was religious or not, but I hoped there was someplace for her to go, someplace warm and sunny . . . The best I could offer was to remember her and others when I got home to Australia. When I got back. It seemed an impossible distance to travel.

The sun peeked out from behind the heavy winter clouds and illuminated the road that stretched out before me. Near the Hudson River I turned south, following streets I’d not walked before near the western edge of Manhattan. I liked the new sights here—desolate, sure, but this was an exploration of the unknown I felt I could handle. It was as if there was someone contriving to send me there, calling me onwards to the south.

After two blocks of weaving through smashed cars and downed buildings the road became impassable. Even so, this morning I felt driven. I trekked these streets with purpose. This wasn’t some false hope, some blind excursion: I was looking for a group of survivors, even though the only evidence of their existence was what Caleb had told me.

If the group he’d told me about was still at Chelsea Piers, then I was relying on my ability to persuade them to leave. I hoped. I’d seen more of human nature in these past two weeks than I had in all my sixteen years; the best of it, and the worst. Was I crazy to expect anything of anyone, that as survivors we shared a common goal? It was my job to convince them, right? I’d persuade them it was safer to leave the city, that we had to get out. I’d take them via the zoo to get Rachel and Felicity and we could head north.

Then I saw something new. At the crossroads before me were three bodies, slumped on the packed snow, but not covered by it. They were fresh: there were traces of color in their cheeks and the blood on their flesh was thin and red, not black and congealed. Anyone could have seen they were not Chasers, and I didn’t think they were the Chasers’ victims—the work was too clean.

I’d known there must have been people who’d survived the attack. I just hadn’t seen them. In true New Yorker fashion, perhaps they’d taken the advice given after 9/11 and barricaded themselves inside. Doors sealed up, windows shuttered, cupboards stocked with all kinds of long-life food. Shelter in place. That was my theory, anyway. But could anyone live that way for long? Maybe here was the answer. These people had had enough: they’d had to break free, to escape, to look for people like me, a way out. Only they hadn’t made it. Had anyone noticed they were missing—and would they be missed now that they were . . . gone?

I tried not to think of this unknown. In fact, I sped up, as if there were people expecting me, waiting anxiously for my safe arrival.

But I didn’t get far. Moments later, I stopped cold. A noise, feet crunching against snow; fast, like many pairs involved in a chase. I listened and looked—nothing. Sound carried by the wind? Shifting rubble cascading nearby? This deserted city was trying to spook me—

No. My fears were real.

Chasers.

I hid in an overturned school bus. Both the front windshield and rear window were in place but there was a black jagged hole of torn steel where the door had been. Dark, deep snow banked up against the side windows, which were almost at ground level.

There was a tear across the palm of my glove, and I knew I’d cut my hand badly—hands that had already taken such a battering. I couldn’t see the wound but through my clen

ched fist I felt the warm, sticky blood. I was scared to breathe, my every motion loud and amplified in here. Through the grimy windshield I watched their feet shuffle as they passed.

The wind, blowing hard from the south, might keep the horizon’s heavy storm away—maybe it would even skip Manhattan altogether. When it looked safe, I dropped down from the bus to the road and tore up a spare T-shirt to use as a bandage. I should have packed a medical kit. I tightened the straps of my backpack and continued south.

At the next intersection the breeze whipped past the corner building and carried with it smoke, the smell of burning gasoline and plastics. I covered my nose and mouth with the front of my sweatshirt, and ran across the intersection and down the next two blocks, before I cracked and took in heaving lungfuls of air. It tasted cold and sharp and clear, dizzying. Gotta keep moving. Gotta get there, get off these streets.

The unknown was getting to me. The familiar parts of Midtown in which I felt so safe now seemed so distant. Sure, I was headed towards something that stirred hope in my gut, but getting there . . .

At each intersection I stopped to check that the coast was clear before crossing the open terrain. I always stayed a few paces away from the dark facades of the storefronts, in case a Chaser jumped out and surprised me. I made sure my footing was on firm ground.

Gunfire crackled from the east. A few single shots, then a continuous burst of machine-gun fire. I recognized it immediately, even though before I arrived in New York I wouldn’t have known the difference between the sound of an assault rifle and a pistol. I had never held a weapon, couldn’t imagine depending on one for my basic protection. But now the need to survive had made me an expert. An image of last night flashed in my mind’s eye: the soldiers at their truck, shooting at the Chasers, the aircraft coming in on an attack run . . .

The gunfire petered out and my awareness of the present returned. Keep moving.

I headed west at 56th. I knew I hadn’t traveled along here before, but it reminded me of so many other streets: the widespread destruction had rendered mismatched city streets uniformly gray and cold and frozen. Manhattan was one big canvas of repeating patterns. I passed a mail truck: which reminded of when I met Caleb. I checked inside it—nothing, no living thing. Nothing but windswept snowdrift and ash.

10

10 3

3 Survivor

Survivor 6

6 The Hunted

The Hunted Quarantine

Quarantine 11

11 The Last Thirteen - 1

The Last Thirteen - 1 Fox Hunt

Fox Hunt 9

9 7

7 Patriot Act

Patriot Act 2

2 Blood Oil

Blood Oil Red Ice

Red Ice Chasers

Chasers Liquid Gold

Liquid Gold 8

8 5

5 The Spy

The Spy Kill Switch

Kill Switch Dark Heart

Dark Heart